what is the way?

This question cannot be given a categorical answer today. The Way is, beyond its history and physical layout, whatever you want it to be. It is worth a few brushstrokes to focus a little on the issue.

THE APOSTLE SANTIAGO

The apostle Santiago (Saint James) is a historical figure. He was a fisherman from the Sea of Galilee, son of Zebedee and brother of Saint John, a favourite disciple of Christ and member of the apostolic college. Given his character, the teacher called him Boanerges, an Aramaic word meaning ‘the son of thunder’. His position allowed him to participate in important episodes of the Christ’s life, such as the Transfiguration on Mount Tabor or the prayer in the Garden of Olives.

His preaching in Hispania is unfounded, and it is a tradition that seeks to justify, a posteriori, the presence of the tomb. In the different narratives, he disembarks at the Cartagena port or at other ports on the Mediterranean Sea. He then travels through a large area of the Iberian Peninsula founding episcopal headquarters. The local Galician traditions mention his passage through Padrón, where he would preach in the Santiaguiño do Monte. They also speak about his arrival in Muxía. The Virgin would go there in a stone boat to announce him that he should return to Jerusalem. A similar miracle, which gave rise to a great centre of worship, is that of the Pilar in Zaragoza.

TRANSFER OF HIS BODY TO GALICIA

James was martyred around 41–44 A.D., when Herod Agrippa I ordered him to be beheaded. This is the beginning of the Translation, the story of the journey that his disciples made with the holy body. They went through the Mediterranean to the Portuguese coast, heading to the estuary of Arousa and Ulla, and landed in Padrón.

The final version of this journey, full of adventures and tricks set by the perfidious Queen Lupa, a pagan lady from that destination, includes two other places near Padrón: Dugium (Duio, Fisterra), where the king who could grant permission to bury the body resided, and the bridge of Nicraria (Negreira) and the mountain Ilicino (Pico Sacro), where they managed to yoke some brave bulls to pull the chariot and move the body to the Libredón, the future Compostela.

DISCOVERY AND VICISSITUDES OF THE TOMB

Due to the lack of news or ancient traditions, historians think that the location of the tomb in the current Compostela was a belated process driven by the urgency of the Reconquest (let us remember the figure of the knightly Santiago, or Matamoros). In fact, it was Beato de Liébana who would end up justifying the finding in his writings. The finding would take place around 830, in the time of Alfonso II el Casto, king of Asturias and Galicia, when Teodomiro, the bishop of Iria Flavia, and Pelayo the hermit saw some lights in that place.

The king moved with his court from Oviedo, capital of the kingdom, and ordered to build the first church on the mausoleum. His successor, Alfonso III, would replace the former church with a larger one, which was destroyed by the Arab leader Almanzor in 997 and rebuilt shortly afterwards.

Finally, the Romanesque cathedral as we know it today was built. There then followed an event that we consider very significant. The Archbishop Xelmírez destroyed the upper part of the mausoleum to reform the main altar. This event is unthinkable if the work was raised by the disciples as affirmed by the tradition; furthermore, he closed the crypt to the faithful.

Sometime later, before the threatening presence of the English troops of Francis Drake and John Norris (1589), who attacked A Coruña, Archbishop Sanclemente hid the relics in a secretive nocturnal manner. No further news of them was heard until the Archbishop Payá y Rico gave orders to excavate the subsoil until they appeared in 1879. After a process of verification, the authenticity of the crypt was confirmed by Pope Leo XIII in 1884 (in the bull Deus Omnipotens), and it became accessible as we know it today.

THE PILGRIMAGE IN THE MIDDLE AGES

We do not have a lot of information about the Way that was followed by the first pilgrims coming from beyond the Pyrenees, though we know of the cases of a Germanic clergyman and the bishop Godescalco of Le Puy, who arrived in 930 and 950 respectively. By the 11th century, however, the French Way was already open. Other itineraries were added to the great pilgrimage, especially in the northern half. With the advance of the Reconquest, they were added from all points of the Iberian Peninsula. In Europe, there is also a large road network that is channelled through four major routes in France: Tours, Vézelay, Le Puy-en-Velay and Arles.

It has always been stressed that the pilgrimage to Compostela surpassed those to Jerusalem and Rome in number, becoming a mass phenomenon. However, in recent years, the crowd that, in the words of the Arab ambassador Ali ben Yusuf (1121), was moving towards the West, has been called into question. The main controversy surrounds the fact that Santiago had a modest population and lacked the capacity to receive so many pilgrims. Therefore, the figure of half a million souls, as estimated in the Holy Years, could have been exaggerated.

DECAY AND RESTORATION

Different events and circumstances have affected the flow of pilgrims since the late Middle Ages: new ideas and forms of piety, revolutions, wars, plagues, etc. In the 16th century, the Reformation caused a great damage to the Compostela sanctuary because Luther ardently opposed pilgrimages and their benefits. However, the Counter-Reformation would exalt the pilgrimages again. The Baroque cathedral and city, a pure triumphal exaltation of the glories of the Religion, were born at this time. The pilgrims were then joined by a large number of professional swindlers and beggars. Their number was so great that it was necessary to regulate the use of rosemary clothing and the maximum stay in hospitals and the city of Santiago.

A second, apparently definitive, decline followed the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars during the 19th century. Bourgeois liberalism does not get along with this form of popular piety, and the ecclesiastical confiscations ended up with monasteries, convents and pious works that supported the hospitals. On the other hand, the transport revolution turned walking into a task for the needy.

When pilgrims seemed to be an image of the past, hitting bottom in the holy year of 1869, Archbishops Payá y Rico and Martín de Herrera managed to rekindle the flame of the Jacobean devotion. Although the apostle Santiago was used in the interests of power during the Franco dictatorship, the last renaissance timidly began in the European post-war period. The common roots of the continent, the values that once forged Europe, were then reassessed, and pilgrims who made the long journey on foot begin to arrive in dribs and drabs. The first Jacobean association was founded in Paris in 1950.

In the 1980s, a providential figure, Elías Valiña, parish priest of O Cebreiro, became a catalyst and animator of this process, as well as the inventor of the yellow arrows. The associations of Amigos del Camino, heirs of the brotherhoods of Santiago, collaborated with him and continued his work.

A qualitative leap took place after the two visits, in 1980 and 1982, of Pope John Paul II to Santiago. However, the qualitative leap took place when the Xunta de Galicia, governed by Manuel Fraga Iribarne, created the Xacobeo project, launched in the Holy Year of 1993.

Since then and until the present, the Way has experienced a continuous growth in the number of pilgrims, but also a substantial mutation in the field of motivations. It has become a new tourist conception that is increasingly being imposed in the new millennium. This circumstance explains the growth of both the experience of short distances and the multiplication of itineraries, some of them of no historical relevance, as well as the emergence of the figure of the turigrin.

We may be currently at a crossroads that could end up defining the future of this thousand-year-old pilgrimage, in which two different worlds now coexist. The years in which the intensive commercial and tourist use of the Way of Saint James could also begin to show signs of exhaustion.

THE STATISTICS

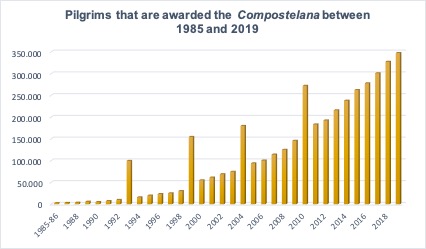

The statistics have only been gathered since 1993 by the Pilgrimage Office of the Cathedral of Santiago because the registration system was still precarious before. However, the figures collected since 1986 do reflect growth, with a somewhat artificial increase in the Holy Years due to the presence of organized groups.

The following table reflects the dazzling evolution from 2,491 pilgrims counted in 1985–1986 to 347,578 in 2019, with peaks in the holy years of 1993, 1999, 2004 and 2010:

THE PILGRIM PROFILE

There are no rigorous studies that clearly establish the motivations of pilgrims. We ourselves are not even clear on the answers. On many occasions one arrives at the Camino with an idea that changes along the route.

Within the framework of the medieval concept of the Homo Viator (a pilgrim of this world who walk towards the eternal goal), the journey was made out of devotion to fulfil a promise or on a penitential foot. The adventure was always an important incentive, though, as well as the professional, political, court-convicted or picaresque foot.

In the present day, the religious and Catholic dimension of the pilgrim has given way to a more Europeanist and ecumenical, purely Christian, conception since the 1980s. Shortly after, with globalization, other interpretations that are better suited to a diffuse spirituality arising from Gnosticism, the new age currents and other ideas that everyone consumes ‘a la carte’ have also impregnated the Camino. Paulo Coelho’s book, El peregrino de Compostela, which has initiated so many pilgrims into the magic of the Way, would be in this vein.

When pilgrims are asked about their reasons for doing the Way, they also mention, among others, sporting, cultural, inner search, learning, meeting others, personal growth and ecology reasons.

In the new millennium, tourist use of the Way occurs on a large scale and is governed by the criteria of promotion, sale and rapid consumption. This has nothing to do with the traditional conception of the pilgrim travelling a sacred route, but rather with a green, cultural, hiking or experiential tourism.

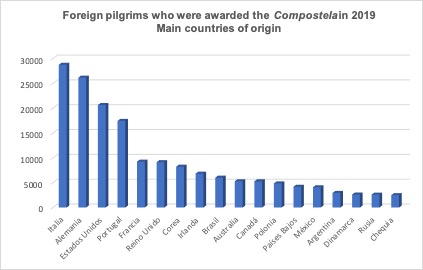

One of the great novelties of the new millennium has been the internationalisation of the Way of Saint James, which has acquired great prestige not only in Europe, but in the Americas, Asia and Oceania. Since 2012, foreigners have outnumbered Spaniards in the global count. Among the main countries of origin, there are some ‘exotic’ countries a priori, a phenomenon that is due to word of mouth, in the first instance, but also to fashions generated by books (Paulo Coelho, Hape Kerkeling, Kim Nam Hee), TV shows or films such as The Way (Emilio Estévez, 2010).

Without taking into account the 145,350 Spanish pilgrims in 2019, the following are the 19 nationalities with the greatest presence on the Way:

A fact that seems very relevant to us, and that confirms the change of era, is that since 2018 women have outnumbered men, currently 51.15% compared to 48.85%. This is something that has never happened before in the history of the pilgrimage.

Other variables also mark a trend, such as the preponderance of pilgrimages on foot compared to those who ride bicycles (it is an almost residual means) or the unstoppable increase of short-distance pilgrimages, which are limited to completing the last 100 km required to obtain the Compostela, associated with the false idea of a ‘complete Way’. As a consequence of this, the average distance travelled by each pilgrim has decreased considerably, from 472 km in 2006 to 304 km in 2019.

Therefore, and if we take into consideration the duration of the pilgrimage, we have three types: the long-distance pilgrimage, which is maintained among foreigners, with journeys of about a month beginning in the Pyrenees, Basque Country, Seville or Lisbon; the medium distance pilgrimage, around 300–400 km long, in which about half a month is used; and the short-distance pilgrimage, less than a week, which today is the preponderant route. A significant fact: 53% of pilgrims in 2019 have only set foot in Galicia.

ONE THOUSAND AND ONE WAYS

If the intensive use of tourism has generated massification in certain sections and times of the year, especially in the vicinity of Santiago, another recent phenomenon has been the excessive multiplication of supposedly Jacobean roads.

Possessed by the yellow arrow fever and trying to legitimise the itineraries in a capricious and unscientific way, every day new routes, links and variants appear, understood more as a supermarket offering than as a serious process to recover historical pilgrimage routes. One need only to review the names of some of these routes to realise that we are dealing with marketing operations. The ultimate interest of these operations is to benefit the places through which the pilgrimage and tourist flood passes.

Our criterion has been to collect the officially recognised paths because the same old history of ‘everything is fine’ or that ‘paths are made by the pilgrims’ does not respond to the criteria with which the Jacobean roads have been recovered in the last decades. A Way of St. James cannot be such if it is not based on the persistence of the transit of pilgrims through time, with the support of a consistent and equally enduring road, reception and devotional infrastructure. There is no point in a whimsical pilgrim, whether Herman Künig or Diego de Torres Villarroel, picking it up in a guide or diary, because a grain does not make a barn. Now, it seems, we are applying the liberal concept of market self-regulation, free competition between destinations and the use of advertising to attract customers in any way, that is, anything goes.

From the above, we can understand that the French Way, which in the first years of the millennium still accounted for 85% of all pilgrims, has now fallen to 54.6%. In the opposite situation is the Portuguese Way, which already accounts for 27.2% of the total of pilgrims and is growing unstoppable with the help of the Porto International Airport.

JUBILEE TIME

It is often claimed that Callixtus II instituted the Jubilee Year of Compostela or Holy Year in 1122, which would be confirmed by Alexander III through the bull Regis Aeterni (1179). This celebration would take place every time the Apostle’s feast of July 25th fell on a Sunday. As with the Holy Door, it seems that this privilege to gain a plenary indulgence was also copied from Rome, where it was instituted in 1300, but in Santiago de Compostela, it is not documented until 1434.

Beyond the origin, the periodicity has been established every 6-11-6-5 years, and the next Jubilee, after the long interval since 2010, will be in 2021; the following ones in 2027, 2032, 2043, etc.

The plenary indulgence has a sacramental character, and in the Holy Years there has been a proliferation of purely Catholic groups from associations, confraternities, parishes or schools, completely changing the style of the ordinary years and greatly increasing their number. During this time, the number of Spaniards in comparison with foreigners also increased.

It is possible to gain the plenary indulgence even if one does not go on pilgrimage on foot, since it is enough to visit the cathedral, receive communion and pray for the Pope’s intentions, and to go to confession 15 days before or after doing so.

THE WAY AND THE GOAL

The goal is to leave (Giuseppe Ungaretti)

If the main value of the Jacobean route were the goal, it would be completely meaningless to complete such long journeys on foot. In fact, the bourgeois pilgrims of the 19th century kept coming to the basilica, but by train or stagecoach. Therefore, the recovery of such a slow and often tiring journey does not only respond to a historicist or romantic feeling. It does not respond only to a taste for trekking either, but to a new way of understanding the meaning of pilgrimage.

The Camino de Santiago has little to do today with the routes leading to other famous Catholic sanctuaries to which pilgrims travel on foot, such as Fátima (Portugal) and Guadalupe (Mexico). In this case, the goal, in many instances, has become an excuse to do the Way, which is what really matters.