the french way

Throughout history, the French Way has been the quintessential pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela in terms of infrastructure, number of pilgrims, temporal continuity and symbolism.

The Reconquista, together with the transfer of the Kingdom’s capital to Leon, facilitated the consolidation of the current route. The Ibañeta Pass through the Pyrenees was established in 1127 at the expense of Somport. The Navarrese monarchs Sancho el Mayor and Sancho Ramírez promoted the repopulation of the town and the passage of pilgrims, as did the monarchs of Leon and Castilia, Fernando I and Alfonso VI. The papacy and the abbey of Cluny collaborated in this undertaking as well. An endless number of monasteries and hospitals, some of royal origin, offered their assistance to the pilgrims, too.

The contemporary revival of the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela began in the 1980s, and during the first two decades of this renaissance, the French Way benefited from indisputable primacy. However, it began to lose ground, percentagewise, against the other routes at the turn of the millennium. In 2005, the French way was chosen by 84.5% of all pilgrims, but fifteen years later, it was only chosen by 54.6%.

On the French Way you will be the star of one of the greatest adventures of humanity, following in the footsteps of the thousands of pilgrims who walked before you, whose souls shine in the Milky Way.

On the French Way you will be the star of one of the greatest adventures of humanity, following in the footsteps of the thousands of pilgrims who walked before you, whose souls shine in the Milky Way.

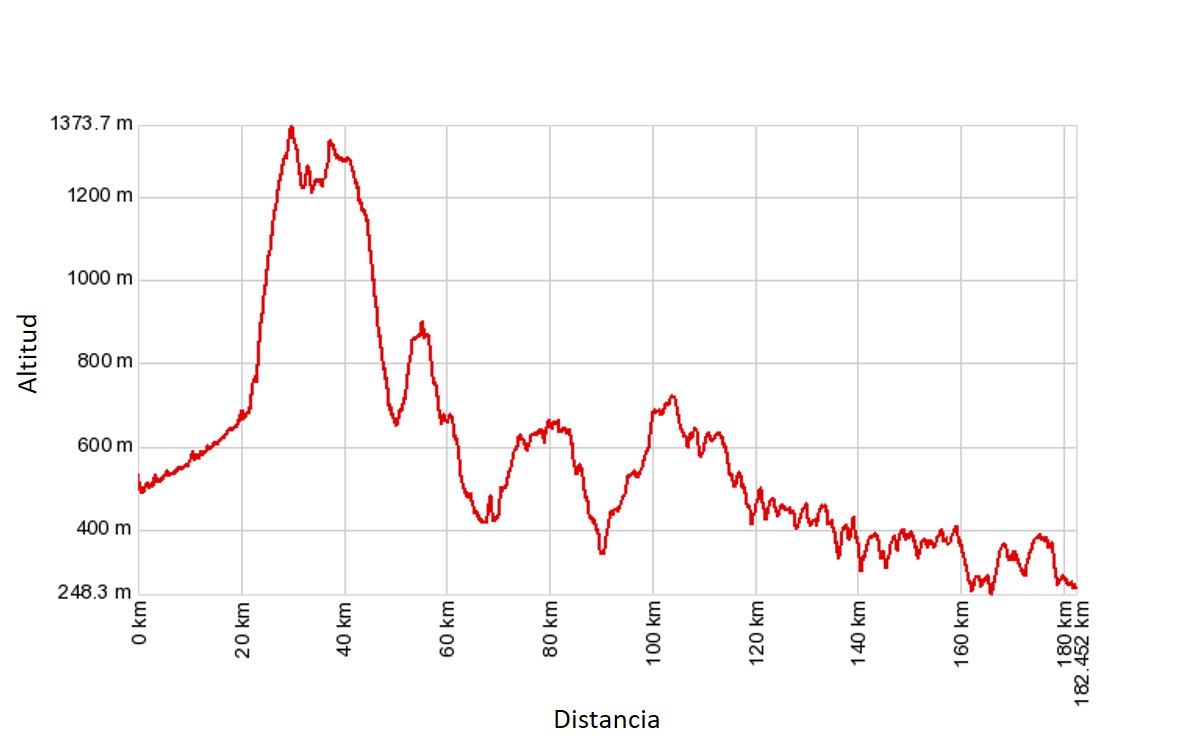

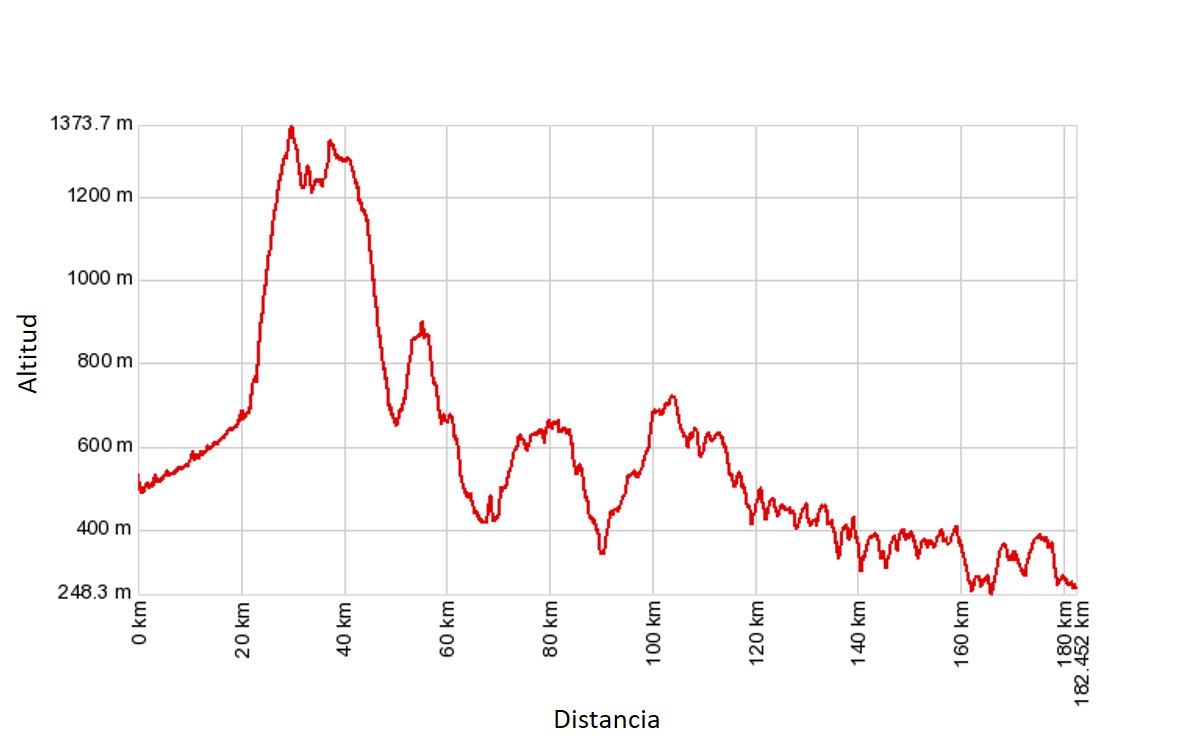

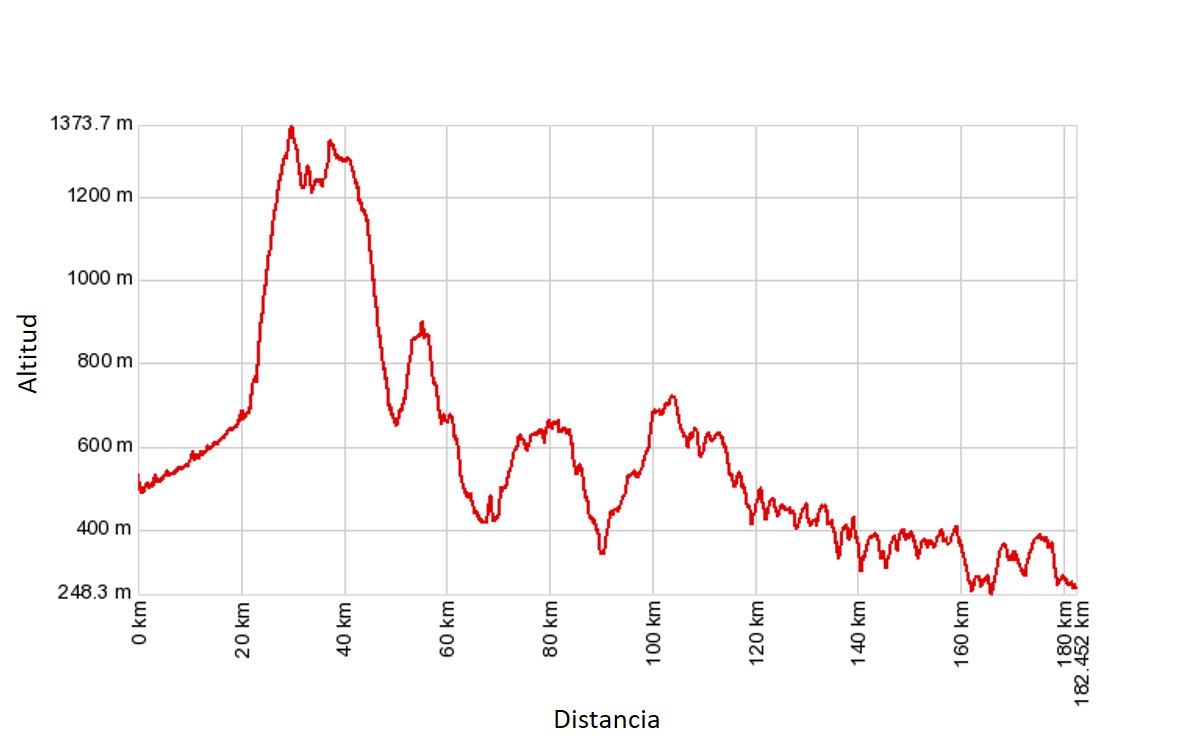

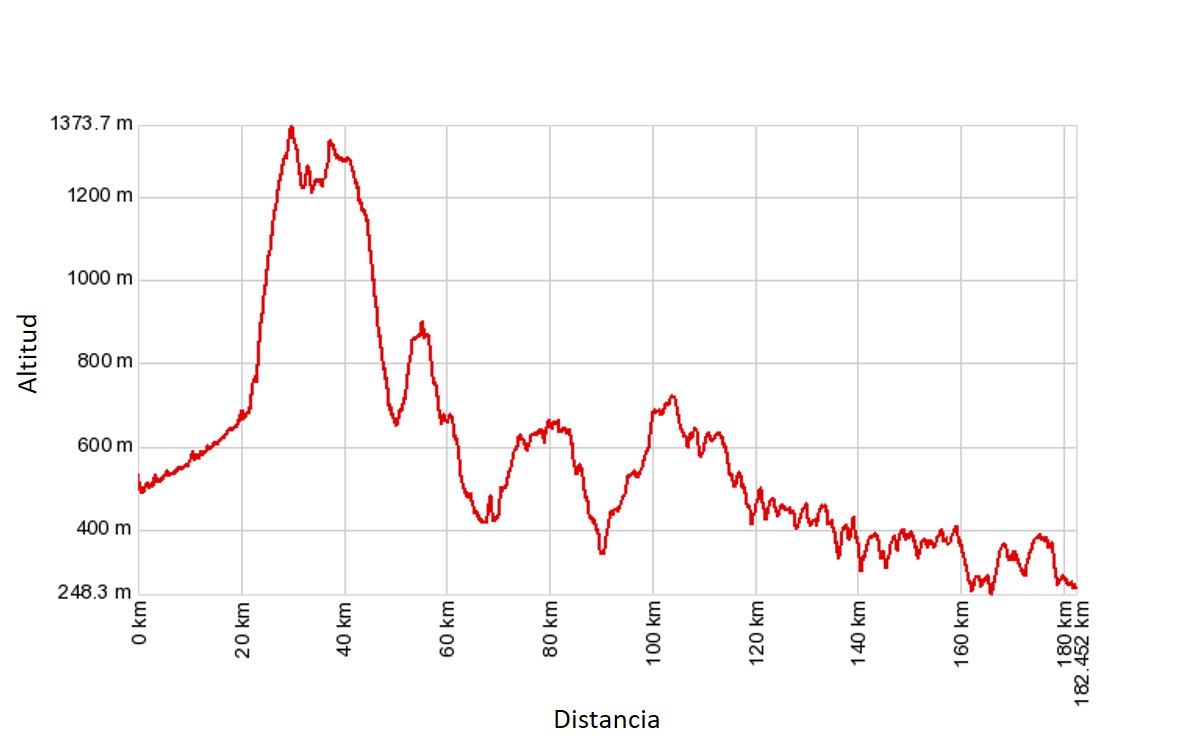

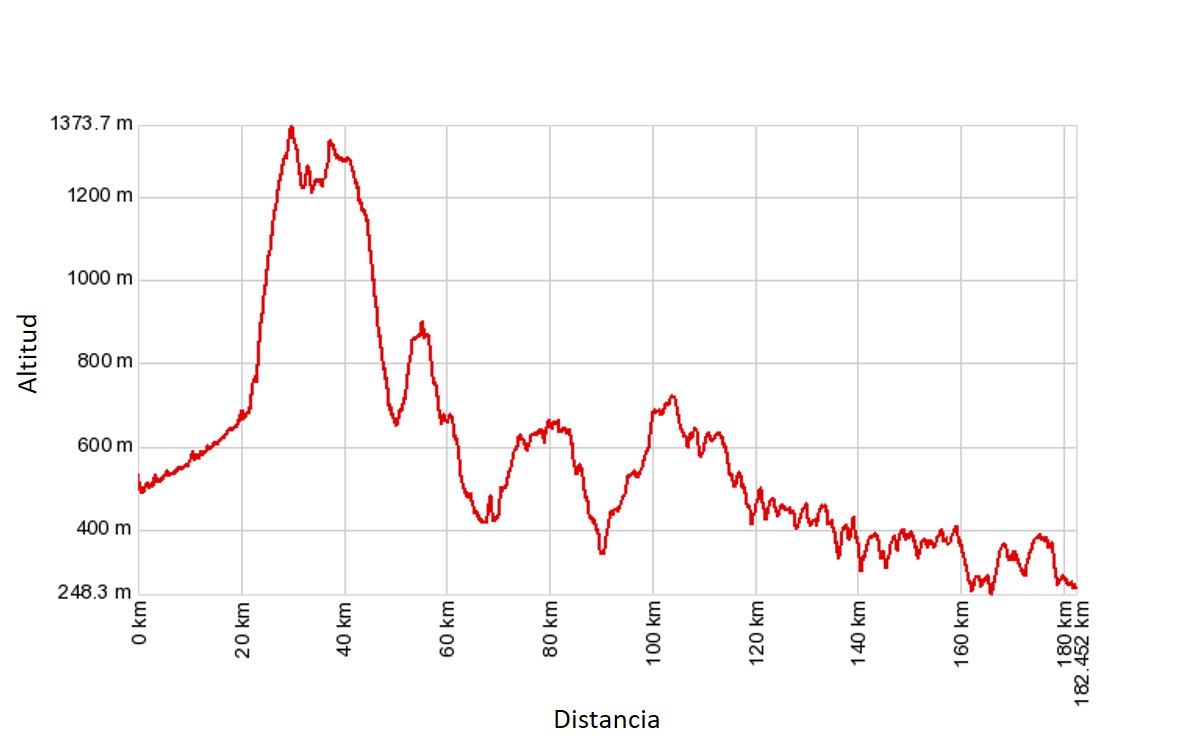

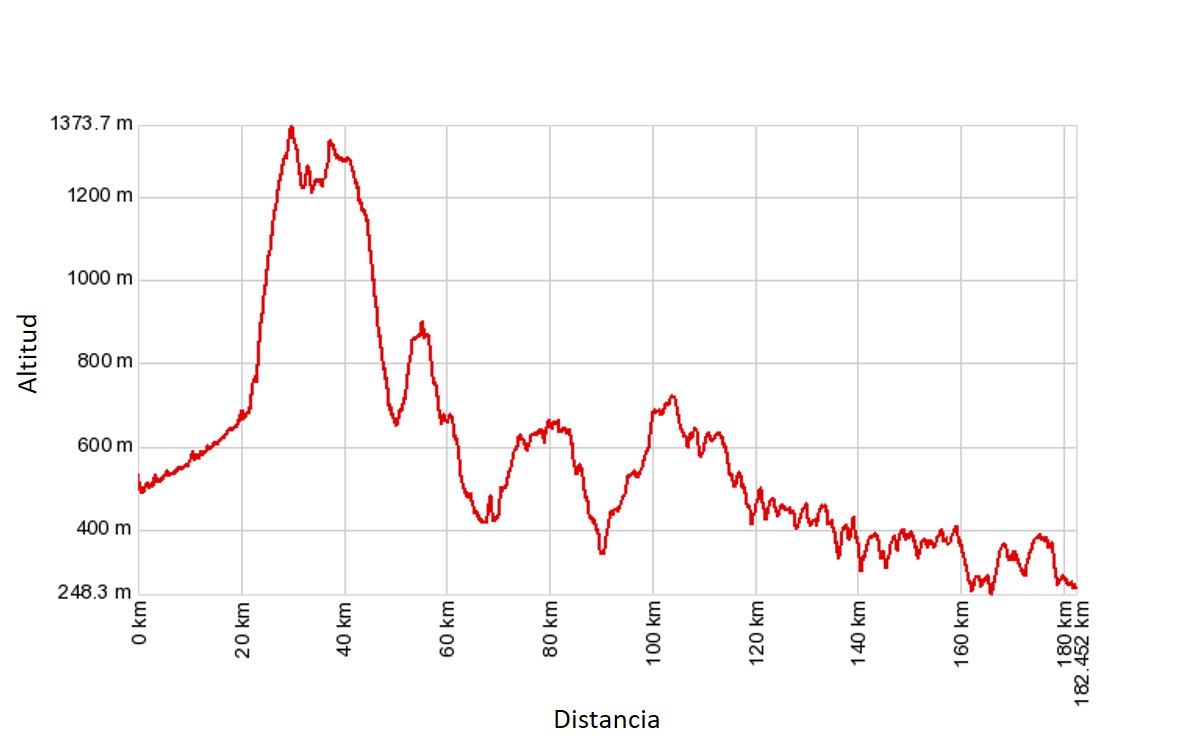

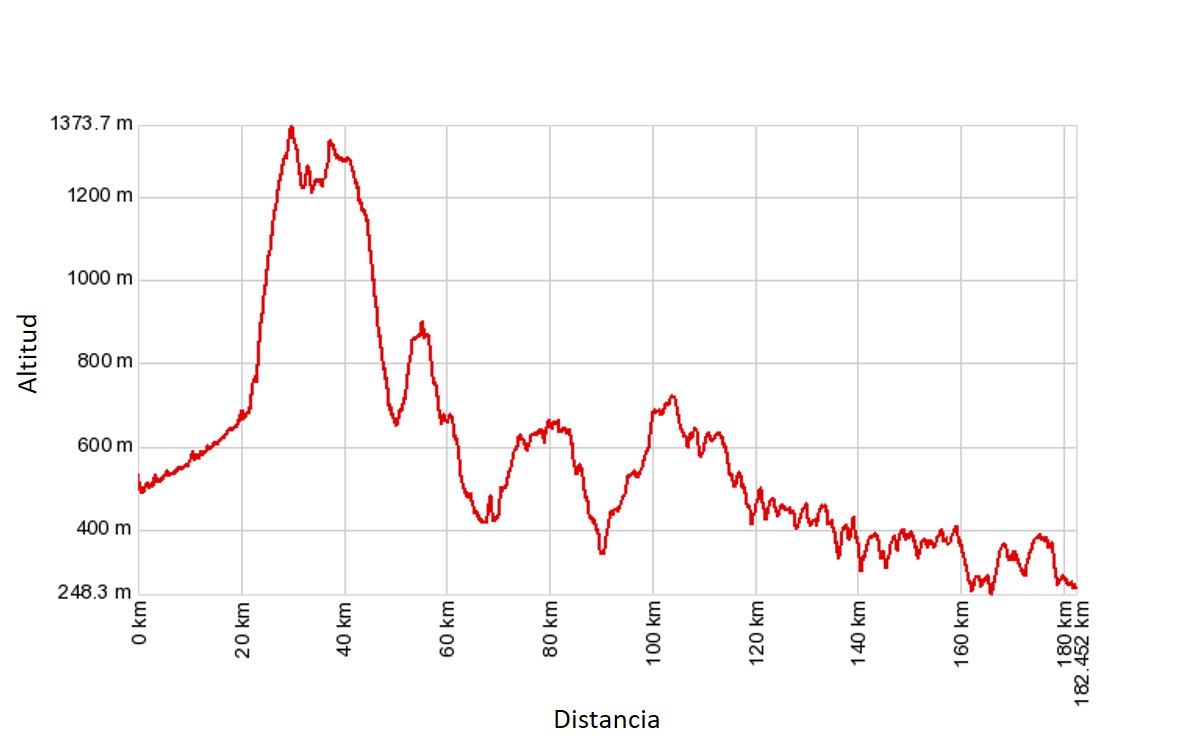

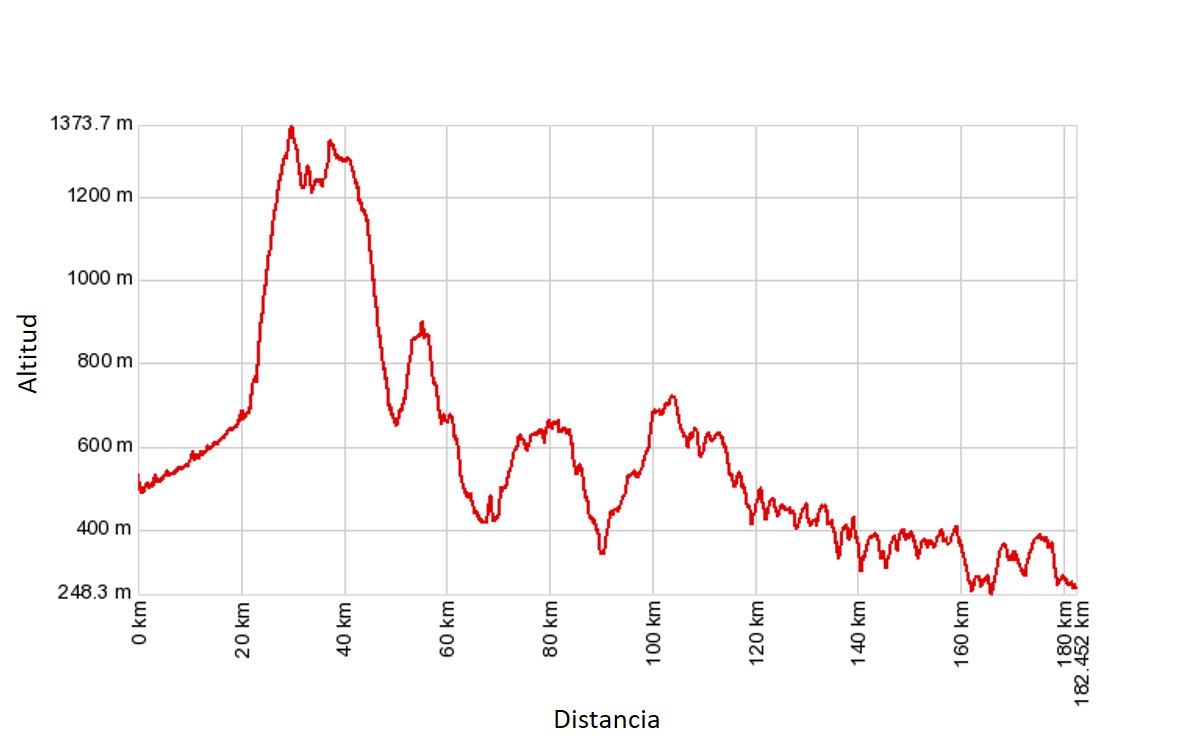

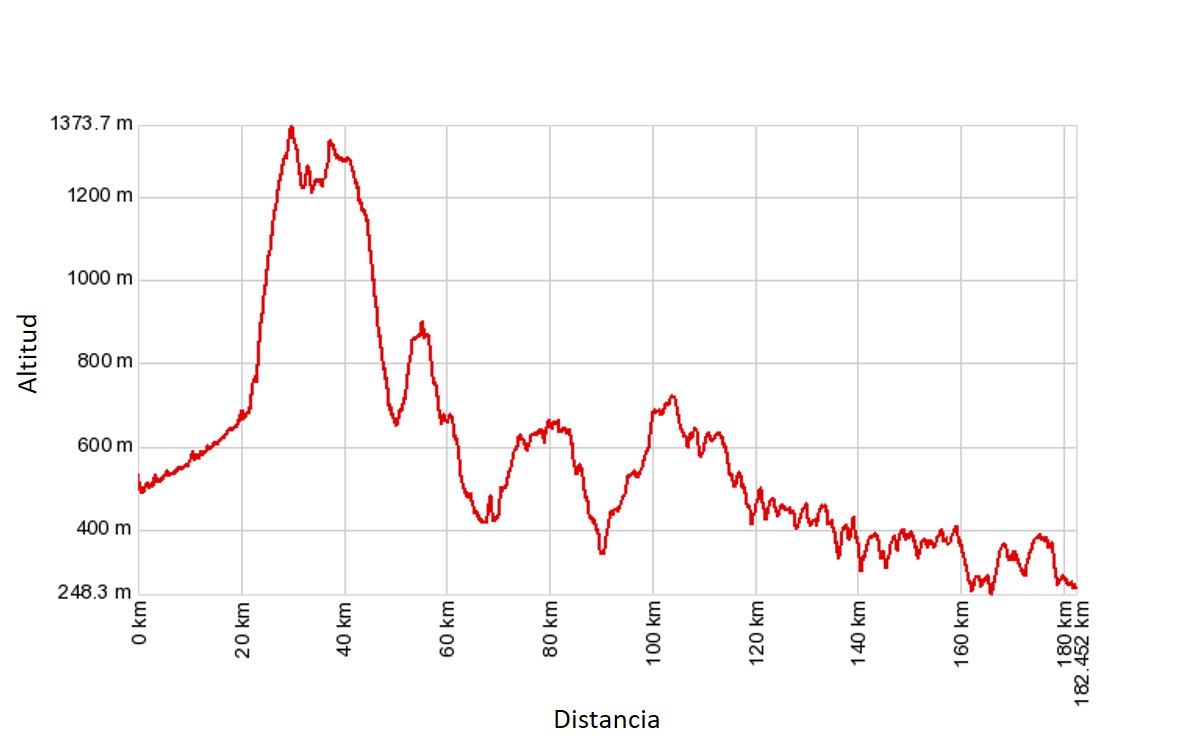

The route stretches between 780 and 880 km from the Pyrenees, along either the Navarre branch or the Aragon branch. The main point of departure is Saint-Jean-pied-de-Port, in the French Basse-Navarre, overlooking Roncesvalles. For the first time in 2019, the 100 km short-distance route from Sarria has surpassed all other points of departure, and the popularity of the original international long-distance route has stagnated.

Sarria is today the main departure point for this route, representing 27.7% of all pilgrims, which shows the route’s drift in terms of commerce and tourists. Fortunately, many of the pilgrims who take the short routes return to the main route to spend more time on it: they discover that going on a pilgrimage is much more than just a short four- or five-day excursion.

The French Way in Galicia is suitable for everyone. The grading of the traditional routes, transformed into homogeneous tracks lacking in personality, has contributed to this. The only relevant geographical feature on the route is the climb to O Cebreiro. There are also ups and downs between Melide and Santiago, but these are minor.

Through the valley of Valcarce and over the hills of A Faba we enter an area of gentle mountains that are the hinge between Os Ancares and O Courel. From here we go down to the wooded Oribio valley, the prelude to the Terra de Sarria. Once we have passed the Miño in Portomarín, we have to cross the region of Ulloa and – already in the province of A Coruña – the regions of Melide and Arzúa, before reaching Compostela.

Sublime are the Oribio valley and its forests, the monastery of Samos, the church of Portomarín, the bridge of Leboreiro, Monte do Gozo…

Sublime are the Oribio valley and its forests, the monastery of Samos, the church of Portomarín, the bridge of Leboreiro, Monte do Gozo…

Despite its historical importance, the French Way in Galicia does not have many monuments. The most outstanding is at the centre of O Cebreiro, the monastery of Samos and the church of San Nicolás in Portomarín.

There is no doubt that the range of services available to pilgrims, and more specifically hostels and other types of accommodation, is enormous, and is growing all the time. Even so, all accommodations may be fully booked at peak times, especially at the end of classic stages.

It takes between seven and nine days to complete the Galician French Way from Villafranca del Bierzo, adding one more day to visit Santiago de Compostela.

HOW TO GET TO VILLAFRANCA DEL BIERZO

HOW TO GET TO VILLAFRANCA DEL BIERZO

– We have chosen Villafranca del Bierzo because it is a relatively well-connected town (Ponferrada is the best connected, with a railway line, and O Cebreiro the worst), but mainly because of its great cultural ties with Galicia. Located at the edge of the valley of Bierzo, it is a gateway to the narrow valley of Valcarce, which heads towards the climb to O Cebreiro.

– You can get there nonstop by bus from Oviedo (3h 50min; 20 euros), León (2h 30min to 2h 45min; 11 euros) or from Madrid (Estación Sur, Intermodal Moncloa or Aeropuerto Adolfo Suárez-T4 in 5h to 6h and 20 min; 32 euros). Alsa is the service provider and also serves the opposite direction from Santiago, via A Coruña and Lugo (3h 25min to 4h; 21 euros).

– If you arrive at Ponferrada by train [see the Winter Way or the Sil Way], you will have to continue by bus to Villafranca (30min, 3.6 euros) or by taxi (20min, 30–35 euros). If you walk, it would be a short and easy stage of 22.3 km – that is, one more day of walking.

sections

villafranca del bierzo – sarria

THE VILLAFRANCA DEL BIERZO–SARRIA STRETCH (69.8 km, through Samos 76 km)

description

The narrow Val Carceris, shaped by the Valcarce River, begins at the exit of Villafranca, where the French Way runs largely parallel to the old N-6 highway, over which the new A-6 passes. Most of the time, the Val Carceris goes through a concrete corridor separated from the highway by prefabricated blocks. When it was constructed, this was an acceptable solution to protect pilgrims from traffic, but today it is considered absurd and contrary to the environment and the essence of the pilgrimage.

After going through the beautiful towns of Pereje and Trabadelo, we turn off towards the valley floor to pass by Vega de Valcarce, the main town in the area. The section with a greater concentration of gallery forests extends to Herrerías, where the mountain pass begins.

Only 9 km remains from here to O Cebreiro, of which 7.5 km are uphill. The stretch along the Roman road heading to A Faba among centenary chestnut trees is the most difficult. After this point, there are no more trees, only meadows and bushes. There is a second village, A Lagúa, to stop for provisions though, before reaching the 1,296-m summit.

There are several reasons why O Cebreiro is connected to myth: its position at the end of the mountain pass; the conservation of a group of pallozas; the pre-Romanesque church; the Eucharistic Miracle (an ancient marvel that few are interested in today); and the great epic work carried out by the priest Elías Valiña (a work which is increasingly fading away) to resurrect the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. In short, it is a critical place on the route.

Myth is only a reflection of a reality. (Los pasos perdidos, Alejo Carpentier)

At this point, the hills are not yet over. From O Cebreiro we still have to climb Alto de San Roque and after that the 1,335-m high Alto do Poio, following Hospital da Condesa, the highest summit of the French Way. These are elevation changes, though, that do not require much effort.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Between O Poio and Fonfría, you have to cross the Rañadoiro highlands before descending towards Triacastela and the Oribio valley. This beautiful stretch runs in the shade of long-lived chestnut trees in its final stretch.

Triacastela is a small wayside town offering a church experience and all kinds of services. From here to Sarria, you can choose from two different routes:

A) The most direct and shortest route through San Xil up to A Balsa, which stands out for the natural beauty of Valdescuro. This route goes to Furela through oak groves, always travelling between small villages.

B) The route through Samos is 6 km longer. This route has the attraction of the Benedictine monastery and the dense forests of the Galician way along the course of the Oribio River.

Both meet again in Aguiada, to continue to Sarria at the edge of a road.

Sarria is the largest town in Galicia on the French Way. It is a small town divided into two differentiated areas: the lower part, filled with long streets full of modern buildings and a promenade and terraces next to the river; and the upper part, comprised of the old town through which runs the Rúa Maior and renowned for its church of El Salvador (13th century), the remaining tower of a castle and the convent of La Madalena (16th and 18th centuries).

Our suggestions

– O Cebreiro. Despite the commercial exploitation of the small enclave, pilgrims will still experience inexpressible emotion when entering this singular gateway to Galicia. Perhaps it is an ancestral feeling forged by tradition, or perhaps it constitutes one of the essential vertices of the way. You have to experience it yourself to get your own reading.

– Just after passing Alto de O Poio, follow the uncrowded new road to Fonfría. It is located higher than the path, which runs parallel to the road, and offers panoramic views of both sides of the mountain range along the Rañadoiro range. Have no fear: it is only 200 m longer than the old road.

-In Samos, go to the Ciprés chapel, which is far from the route but only 200 m from the monastery. It is a Mozarabic building from the 10th century accompanied by a slender cypress catalogued as one of the oldest trees in Spain (some people consider it may be one thousand years old). Of course, you should also think about visiting the monastery, which has a small cloister from the 16th century and a neoclassical church and a larger cloister from the 18th century.

– In Sarria the number of pilgrims suddenly doubles. Much of its activity revolves around the pilgrimage route so, despite the hustle and bustle, you will feel at home. If you are missing something from your equipment, go to the Pilgrim Library, a specialised store that supplies pilgrims from all over the world.

sarria – melide

THE SARRIA–MELIDE STRETCH (63 km)

description

The Naked Jungle! [title of a 1954 film, starring Charlton Heston, in which these voracious ants ravaged everything they found in their path, metaphor of the grocery that suffers in Camino between Sarria and Santiago]

Many pilgrims describe the stretch approaching the Miño River as one of the most beautiful sections of the French Way. It has many attractions, including meadows, temperate broad-leaf forests and rural enclaves that have been revitalised to serve the crowds, all of which make it a very pleasant stretch.

Shortly after leaving Sarria, the way crosses the Áspera Bridge and a 13th-century factory. Approaching the railway, there is a branch that crosses Zanfoga to continue to A Pena. Although this option is slightly shorter, this route is not worth following as it consists of more asphalt.

The main road crosses uphill among chestnut trees to the Paredes hill fort and passes very close to the Romanesque church of Barbadelo. The carballeiras [oak forests in Galician] remain along the route up to the mill of Marzán. This branch comes after crossing the LU-633 road and passing a good number of small rural villages whose names will be impossible to remember. Among these villages we reach the 100-km mark, the most photographed en route. Portomarín awaits us on the other side of the Miño.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Once the concrete bridge is crossed, the path goes up through an arch in the medieval Pons Minea, which was recovered before the damming of the river flooded the old Portomarín. Some of the town monuments were transferred into the new 60s colonial-style village so as not to completely lose its historical references. Today, this is one of the towns with the most hostels along the whole way.

From the Miño River, you can climb nonstop to the Serra de Ligonde, a very gentle walk without big slopes. The pine groves gain ground, but as it is a livestock area, the meadows and the fodder crops are also maintained.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

After crossing the N-640 on the other side of the mountain, a change of panorama is perceptible. We are entering the region of A Ulloa, famous for its cheese and chestnut production. In Ligonde, the place where there once was a cemetery for pilgrims is marked with a cross. Although the eucalyptus trees have a growing presence, the landscape is still pleasant as far as Palas de Rei. Here, we will see the Pico Sacro for the first time.

Between the modern centre of Palas and Melide, we have to overcome the unfriendly A-54 motorway junction and later pass through San Xulián do Camiño with its Romanesque church. The temperate broad-leaf forests continue until the beginning of the province of A Coruña, which is entered by the road of Leboreiro, today underground.

After passing through Leboreiro with its medieval church and bridge, we start walking through a stony, barren terrain, the Gándara de Melide. Here, the creation of a business estate was unfortunately authorised in the middle of the French Way, camouflaged in a plantation of small trees.

In Furelos, we cross the four-arched medieval bridge, originally from the 12th century, over the river. From here, there is only one town left, Melide. The town has a small historical area but, above all, it is famous for its pulpeiras [octopus restaurants in Galician]. Here is where the French Way meets the PRIMITIVE WAY.

Our suggestions

– Get your credencial [pilgrim’s passport] stamped at the Romanesque church Barbadelo (12th–13th centuries). Besides being dedicated to Santiago, represented as a pilgrim in the altarpiece, the church belonged to a monastery. Among its curiosities are the tympanum, where you will see some very Celtic interlacing, and the tower embedded in the building and supported by two arches with historic capitals.

– The main monument of Portomarín, a must see, is the church of San Nicolás. It belonged to the order of St John of Jerusalem and responds to the concept of the temple-fortress, with a very high single nave illuminated by two rose windows. The western doorway is a synthesis of the glory described in the Apocalypse, with the Pantocrator and 24 elderly musicians.

– Behind the village of Castromaior, next to the way, stands the largest hill fort of Galicia, giving the town its name. You will be able to appreciate its structure, as it has been partially excavated. It has up to six defensive enclosures and many houses with a square or rectangular floor plan, which certifies its Romanisation.

– Don’t forget to stop for a moment before a very humble but richly symbolic monument: the cruceiro de Lameiros. It was built in 1674, and the cross shows the crucified Jesus Christ and, on the opposite side, a Pieta. At the base, the elements of the Passion were carved, including a skull among them.

– The small village of Furelos stands out because of its medieval bridge, but lately it has also become famous for the Crucifix of its parish church, San Xoán. The most outstanding feature of this Crucifix is its unnailed arm, like the famous image of Segovia.

You can add its seal to your credencial [prilgrim’s passport] to carry in your credentials.

– Melide is particularly well known among pilgrims because of its pulpeiras, and more specifically because of Ezequiel’s, which maintains the traditional style of such places with their tables and benches. Don’t miss it – it’s one of the mythical rituals of the way!

melide – santiago

THE MELIDE-SANTIAGO DE COMPOSTELA STRETCH (53,5 km)

description

As soon as we leave Melide behind, we pass by the Romanesque church of Santa Maria (12th century), with its one nave and semi-circular apse. Inside, a medieval altar is preserved, as well as murals from the beginning of the 16th century representing the Trinity and the Tetramorphs.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Once the Catasol stream has been crossed, the path goes up to Raído, and we go down again to Boente next to its fountain and church of Santiago. A steep drop takes us to the Boente River, and the roller coaster – which will definitely make you sweat – continues towards Castañeda. An extensive eucalyptus plantation separates this valley from the next, and all of them like transversal to the way.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

On the banks of the Iso River, we meet again the pairing of bridge and hospital. The subsequent climb to Arzúa is hard. The village, modern and stretched out over the N-547, features a lively boulevard and the Gothic Madalena chapel (14th century). In Arzúa, the French Way meets the main branch of the NORTH WAY.

You have to continue along broken terrain to cross the As Barrosas stream, which is followed by a steep climb. Here, eucalyptus plantations coexist with cattle pastures, although there are usually oak trees along the way.

The toponyms associated with the path mark this route: Tabernavella, Calzada, Calle, A Brea, and A Rúa. In Salceda, you can see a simple monument memorialising the pilgrim Guillermo Watt, who died here in 1993; it is not the only one, as there are several on the French Way in recent years, which is a contrast with the anonymity of those who perished along the route in the past.

From O Empalme, a crossroads with bars and restaurants, you go down to Santa Irene, where the fountain and chapel are often ignored by pilgrims. A common final stage for making the final jump to Santiago is O Pedrouzo, the capital of the council of O Pino. It is another modern centre, full of hostels and pensions, grouped around the national road.

The last stages take us to Amenal, where the way up to Barreira Peak begins. A second business park was also planned here, as in Melide – it seems we do not learn from the mistakes of the past to protect the way! The route was covered by the airport of Lavacolla and passes under the access road.

In Lavacolla, pilgrims historically used to wash themselves in its modest stream before reaching Compostela. The last slope extends to Vilamaior. The way continues through a new eucalyptus plantation to San Marcos and its chapel and to Monte do Gozo. Finally, the pilgrims can see the cathedral towers and the final goal of the pilgrimage.

There is little to say about the entrance to Santiago, although the route is being improved for the holy year of 2021. In a way, at this point, the route is unimportant because what matters is about to appear. We will not get into details about the section between the San Lázaro quarter and the charming Rúa de San Pedro. This street leads to the old town through the Porta do Camiño. The Casas Reais, Praza de Cervantes and Acibechería leave you in front of the cathedral. You have arrived at Santiago de Compostela.

All good things come to an end. However, in this case, the short final stages will not seem twice as good, but rather frustrating as we have already reached the point of the pilgrimage. Some will be satisfied by meeting the goal itself, but to the most restless people, completing the pilgrimage will seem like only the beginning, possibly of a farewell.

We have forgotten that our only goal is to live and that life is what we do every day and at all hours of the day we achieve our real goal if we live. (Jean Giono)

Our suggestions

– Breathe deeply and hope that the section along the Catasol stream, an orchard of alders, oaks and birches, never ends. You will cross its rustic pontella (which can’t quite be classified as a bridge) in a scene that could be the dwelling place of nymphs.

– Visit the church of Santiago de Boente, with its popular and nice image of Santiago Peregrino (19th century). He will stay with you forever, because every pilgrim is given a holy card.

– Whether you stay there or not, try to stop at the public hostel in Ribadiso next to the medieval bridge with an arch. The restoration of the old buildings, which has been a hospital for pilgrims since the 13th century, has been a complete success on the part of the Xunta de Galicia’s government. The river serves as a natural swimming spot.

– In Arzúa be sure to try the local cow’s cheese. Protected under the designation of origin, Arzúa-Ulloa, with a soft texture and cylindrical, flattened form, it is, along with the tetilla cheese, the best-known cheese of Galicia. We advise you try the farmhouse kind made with raw milk, if possible. Enjoy!

– It’s shocking that today we don’t know for sure exactly where Monte do Gozo was. Of French origin (Montjoie), it is called Monxoi in Galician. In the past, it gave rise to many emotions. It was also witnessed crazy races to determine who would be the first to see the towers of the cathedral and be proclaimed by his companions ‘the king of the retinue’. It’s fine to settle for the sculptural monument in memory of John Paul II’s visit (1989) at the edge of the way, but from the neighbouring hill, decorated with the figures of ecstatic pilgrims, the experience is much more rewarding.